Foreword by Nguyễn Huy Thiệp (Vietnamese writer*)

Vietnamese We - Beyond Divides is a poignant visual story on a people told through image, text and sound, by a Vietnamese man who lives in Paris. For various reasons, I found this unusual art book known as zixbook both moving and thought-provoking.

As a writer, I understand the madness that can drive a man put pen to paper or grab a camera. And how, from that moment, as he emerges from anonymity, he may become a danger both to himself and to other people.

The author left Vietnam as a young boy; he grew up in France, where he still lives and works. His memories of Vietnam were quite vague. Then one day, returning to the land of his birth, a quite different world appeared before him. This new vision revealed an inner world which, in France, had lain dormant within him, or that he had perhaps suppressed deep in his subconscious. And this is how he discovered his vocation as an artist.

There are some books that have changed, and even shattered, the lives of their authors. There they are, quietly living their ordinary lives in this world, when one day, without really knowing why, they start creating a book. Such a book may be the author’s downfall; or it may bring him something that he never could have imagined, and certainly never dreamed of. Whether this is a good or a bad thing, only Heaven, and himself, can tell.

Vietnamese We - Beyond Divides uniquely symbolizes an authentic people in pictures but also tells us underneath the story of a return to the past, to the homeland, to the origins of a Vietnamese man living in exile. I read it with real pleasure yet also with envy. For me, this art book held many surprises. I hope that for you too, readers all over the world who have a place in your hearts for Vietnam, the zixbook will take you unawares.

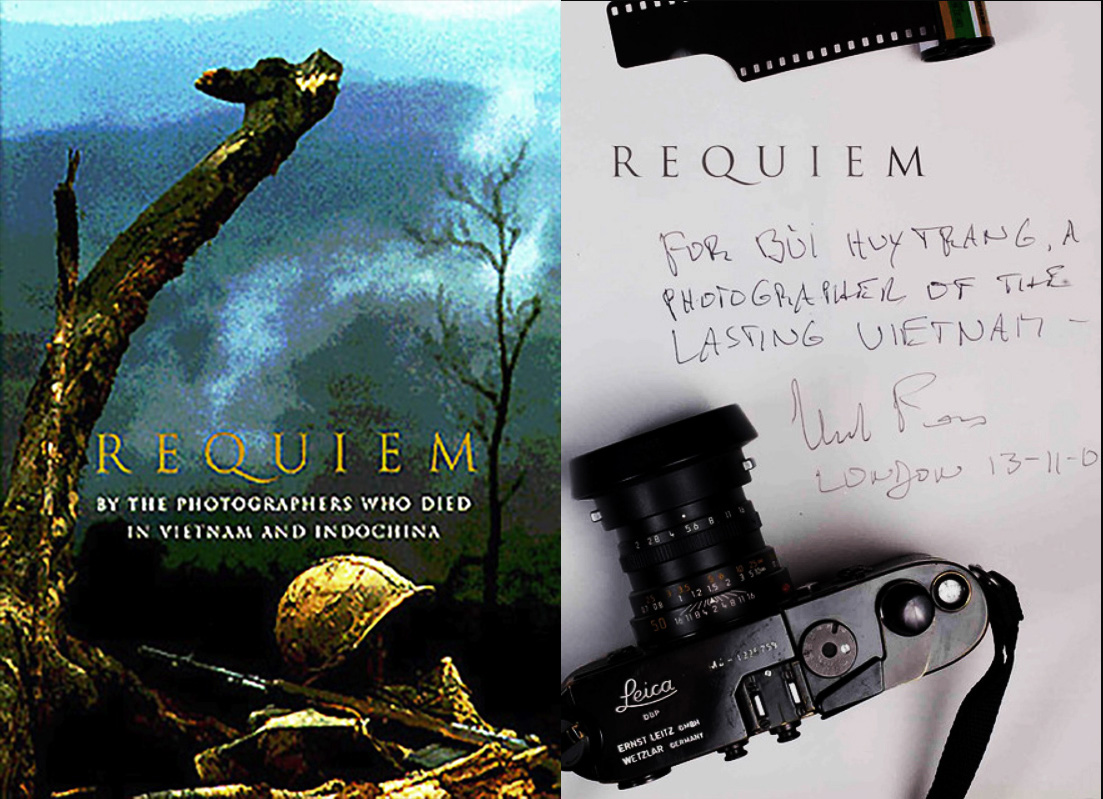

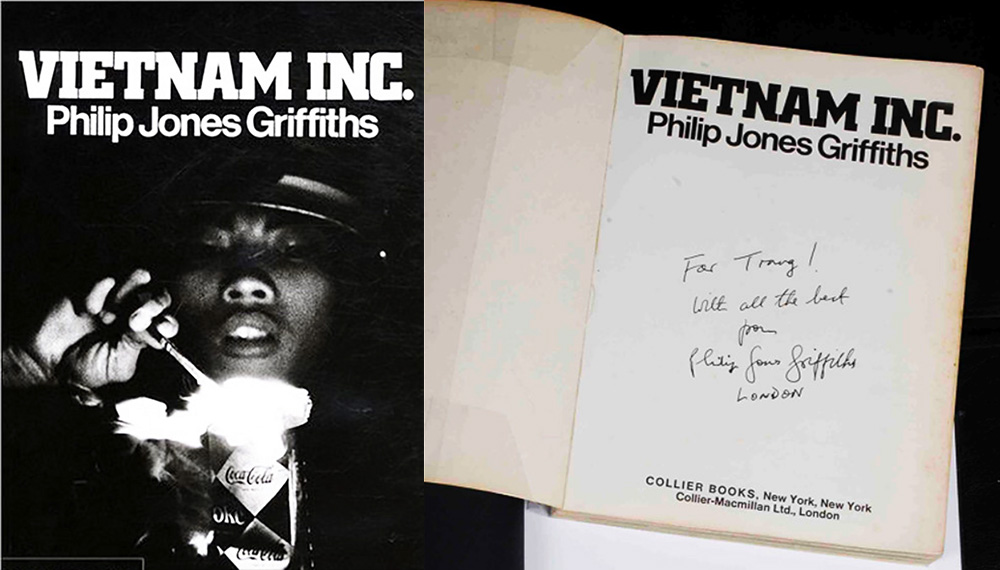

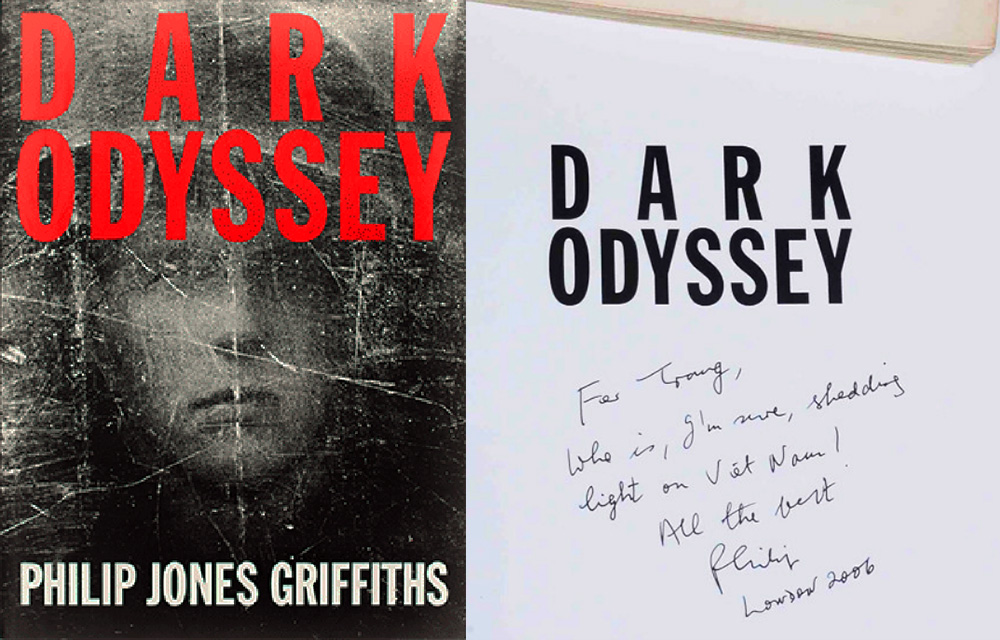

I wish Bùi Huy Trang, the author of this atypical book, good luck as he embarks upon his new adventure.

* Born in 1950 in Hanoi and world-acclaimed, this prominent clear-sighted author was awarded the Literature and Art medal by the French government on July 9,2007 in Hanoi and the Nonino Risit d'Âur Prize on January 26, 2008 in Italy. Several of his collection of short stories (The General Retires, Without a King, Love Story Told on a Rainy Night...) have been translated and published by Oxford University Press and Curbstone Press, respectively in 1992 and 2003.

Point of view by Lady Borton (American writer*)

Translators are servants. They labor in silence, mining a source, conveying its soul to others. Bùi Huy Trang is a photographer and a poet, but he is also a translator, bringing us a depth of soul we seldom see.

Mr. Trang has titled his work in English, Vietnamese, and French. Regardless of language, the phrases Vietnamese We - Beyond Divides, Người Việt Nam chúng tôi - Bên kia bờ chia rẽ and Nous autres Vietnamiens - Au-delà des clivages carry several meanings. In their most restricted usage, they may refer only to the Việt (or Kinh), one of Vietnam’s fifty-five ethnic groups. More broadly, they may denote citizens of a nation, Việt Nam, and thus include all its ethnic groups. More broadly still, these phrases may embrace all people of Vietnamese heritage wherever they live.

In this work, Bùi Huy Trang concentrates on lives of ordinary Kinh (Việt) in Vietnam yet also introduces other ethnic groups. He takes us on a nationwide tour of Vietnam – north, center, and south; lowlands, midlands, and highlands. In such a unique manner he also reveals the ineffable homesickness of overseas Vietnamese living in the world.

The result is a tour de force, for Bùi Huy Trang translates the quintessential yet untranslatable Vietnamese phrase: Quê Hương.

Quê Hương does not mean birth place. Nor is the phrase adequately rendered by homeland. Except for a few matrilineal ethnic minority groups, Quê Hương refers to the father’s ancestral home.

Vietnamese believe the living can access the spirits of the departed as a source of wisdom and guidance. Each household honors deceased ancestors with a family altar displaying candles or lamps, fruits, flowers, and an incense urn. The family adds to the altar special dishes, votive money, and other ceremonial objects (e.g. clothes, motorcycles) fashioned from paper on a family member’s death-day anniversary and at Tết to welcome the ancestors back home to celebrate the Lunar New Year.

Vietnamese both inside and outside the country may have never visited their Quê Hương, the site of their ancestors’ graves. Nevertheless, their ancestors’ spirits stretch across time and space, drawing the thoughts of Vietnamese back to the source of their family’s soul, back to the source of their very own soul.

With Vietnamese We - Beyond Divides / Người Việt Nam chúng tôi - Bên kia bờ chia rẽ / Nous autres Vietnamiens - Au-delà des clivages, we tour Vietnam and the world. We experience the essence of life for ordinary Vietnamese citizens, both Kinh and other ethnic groups. We reach across borders and explore a heritage. We delve into a wider vision of Quê Hương with Bùi Huy Trang as he explores his heritage and translates the source of his own soul.

* As a true lover of Vietnam born in 1942, she is a journalist-author, academic and charity activist who talks authoritatively about this country from a unique perspective, having incredibly lived there both during and after the war and learnt its culture and language. Her books include After Sorrow: An American Among the Vietnamese (1995), Sensing the Enemy: An American Woman Among the Boat People of Vietnam (1984) and Hồ Chí Minh: A Journey (2007).

Afterword by Jean-Claude Guillebaud (French journalist and writer*)

To get straight to the point, I love both the concept of zixbook, invented by Bùi Huy Trang, and the one hundred photos he has selected to portray Vietnam. Each seems the ideal medium for evoking this country – and more specifically its people – to which I have, for such a long time, been attached in a thousand myriad ways. Just writing that makes me think of the extraordinary agility of the Vietnamese, who, just like ourselves, are now immersed in the overwhelmingly bewildering age of modern technology. It also makes me think of the unique attachment to tradition of this people, marked more than any other by its history and tragedy.

I first discovered Vietnam in the late 1960s, when the “Thirty Years’ war” was raging. Ever since, I have never missed a chance to go back, and back and back again. Why? For a reason which, it seems to me, the hurried tourist barely notices. In Vietnam the sheer tenacity of the peasant, the storekeeper, the soldier comes hand-in-hand with an indefinable beauty, in the landscape, naturally, but also in a certain softness, a smile, a particular elegance. The Vietnamese thus give the impression that daily life is something of a game, even in the very harshest circumstances.

The insignificant activities of everyday life - eating, driving a scooter, irrigating a rice field, picking rice - always seem to be performed as if with a slight shift to the side, a space for amusement, an imperceptible manner of “playing a game” which, no doubt, helps lighten the burden. Perhaps my love for the country makes me naive, but I’ve always been drawn to that infinitesimal trace of “play”, a tremor that adds to the country’s charm, and which is something hinted at in Bùi Huy Trang’s photographs. The Vietnamese, for all their seriousness and tenacity, seem never to take themselves completely seriously. There is something childlike in the country, and not simply because, demographically-speaking, it is has one of the youngest populations in the world. I often think of that minuscule triangle of skin revealed by the woman’s ao dai, between the trouser belt and the split down the sides of the tunic, imagining it to be part of a highly subtle game played between a man and a woman.

As for the landscapes of Vietnam, however extraordinarily varied they are, the Delta plains, the embossed relief of the High Plateaus, the beaches of Nha Trang and Da Nang, that imperceptible trace of the “game” is everywhere. It is so intimately bound to the beauty that it is easy to understand the genuine enchantment felt from the nineteenth century on by Western “explorers” of Indochina. As we can see in their travel writings, published at the time in L’Illustration, and from which I learned a great deal, especially the writings of Dr. Charles-Édouard Hocquard who, from February 1884 to April 1886, took part in the Tonkin Campaign. Apart from his impeccable erudition, his accounts reflect a something like a bedazzled passion toward the land and the people, a passion that was shared throughout the twentieth century by several generations of civil servants, soldiers, journalists and administrative staff all so in love with Indochina that people started to call them “Asiatics”. It’s disturbing to realize that, in Hocquard’s writings, like those of Jules Ferry, we find descriptions of the “magic of Indochina” prefiguring the descriptions of the great novelists and journalists of the interwar period and the 1940s, such as Lucien Bodard, Paul Mus, Albert Londres, Jean Lacouture and many others.

At the end of the nineteenth century, these fascinated explorers were already writing of the rice fields stretching to infinity, framed by cloud-topped mountains. They described the meticulous honeycomb compartmentalization which, centimeter by centimeter, disciplines land and water as far as the eye can see; crisscrossed by a network of clay dikes across which women hurry, their shoulders bent under the weight of their bamboo yoke; the actions and rhythms – two men stand opposite each other, rhythmically swinging their irrigation buckets at the end of a rope, the yoked buffalo cautiously padding knee-deep through the water, and other buffalo caked in dried mud, monstrous statues of clay that obey the orders of children who, as if at play, harness them by the nostrils or squat on their boney backs like Indian elephant drivers. They also wrote of the flotillas of ducks that cast off in their thousands across the rivers and lakes.

Such splendor, described in this way, was not just some endlessly hashed out color print, it already was Vietnam. It was that indestructible identity of the Vietnamese, including that trace of play, which will survive through whatever tragedies the future holds in store. But that is just one facet of reality. Without denying their past, the Vietnamese of today, to whom Bùi Huy Trang has dedicated his photos, don’t want us to forget that they also live in a country “just like any other country”, with all its problems, its injustices, its daily life and its plans for the future. Rooted in the present, modern Vietnam, zixbook - also - is presented as a sort of technological and editorial “game”. As you may imagine, I rather like that.

* Born in Algiers in 1944, he is an award-winning author, journalist, editor and lecturer known for his work in the world of ideas. A former war correspondent, he fell in love with Vietnam and Ethiopia, and was awarded the Albert Londres Prize in 1972 for his coverage of the Vietnam War. A one-time Sixties liberal, he has been a leading voice for the European Left for 25 years, analyzing and writing about social and political issues from a multinational perspective. He also directed the international organization Reporters without Borders (1987-1993). Since 2008 he has been a member of the supervisory board of the press group Bayard Presse. In 2016 he served as President of the Jury for the Bayeux-Calvados Award for War Correspondents. His books include: Return to Vietnam (1994), The Tyranny of Pleasure (1999) and Re-founding the World: A Western Testament (2001).